Apache Kafka

Table of Contents

- 1. はじめよう

- 2. API

- 3. 設定

- 3.1. ブローカ設定

broker.idlog.dirsportzookeeper.connectmessage.max.bytesnum.network.threadsnum.io.threadsbackground.threadsqueued.max.requestshost.nameadvertised.host.nameadvertised.portsocket.send.buffer.bytessocket.receive.buffer.bytessocket.request.max.bytesnum.partitionslog.segment.byteslog.roll.{ms,hours}log.cleanup.policylog.retention.{ms,minutes,hours}log.retention.byteslog.retention.check.interval.mslog.cleaner.enablelog.cleaner.threadslog.cleaner.io.max.bytes.per.secondlog.cleaner.dedupe.buffer.sizelog.cleaner.io.buffer.sizelog.cleaner.io.buffer.load.factorlog.cleaner.backoff.mslog.cleaner.min.cleanable.ratiolog.cleaner.delete.retention.mslog.index.size.max.byteslog.index.interval.byteslog.flush.interval.messageslog.flush.scheduler.interval.mslog.flush.interval.mslog.delete.delay.mslog.flush.offset.checkpoint.interval.mslog.segment.delete.delay.msauto.create.topics.enablecontroller.socket.timeout.mscontroller.message.queue.sizedefault.replication.factorreplica.lag.time.max.msreplica.lag.max.messagesreplica.socket.timeout.msreplica.socket.receive.buffer.bytesreplica.fetch.max.bytesreplica.fetch.wait.max.msreplica.fetch.min.bytesnum.replica.fetchersreplica.high.watermark.checkpoint.interval.msfetch.purgatory.purge.interval.requestsproducer.purgatory.purge.interval.requestszookeeper.session.timeout.mszookeeper.connection.timeout.mszookeeper.sync.time.mscontrolled.shutdown.enablecontrolled.shutdown.max.retriescontrolled.shutdown.retry.backoff.msauto.leader.rebalance.enableleader.imbalance.per.broker.percentageleader.imbalance.check.interval.secondsoffset.metadata.max.bytesmax.connections.per.ipmax.connections.per.ip.overridesconnections.max.idle.mslog.roll.jitter.{ms,hours}num.recovery.threads.per.data.dirunclean.leader.election.enabledelete.topic.enableoffsets.topic.num.partitionsoffsets.topic.retention.minutesoffsets.retention.check.interval.msoffsets.topic.replication.factoroffsets.topic.segment.bytesoffsets.load.buffer.sizeoffsets.commit.required.acksoffsets.commit.timeout.ms- Topic-level configuration

- 3.2. Consumer Configs

- group.id

- zookeeper.connect

- consumer.id

- socket.timeout.ms

- socket.receive.buffer.bytes

- fetch.message.max.bytes

- num.consumer.fetchers

- auto.commit.enable

- auto.commit.interval.ms

- queued.max.message.chunks

- rebalance.max.retries

- fetch.min.bytes

- fetch.wait.max.ms

- rebalance.backoff.ms

- refresh.leader.backoff.ms

- auto.offset.reset

- consumer.timeout.ms

- exclude.internal.topics

- partition.assignment.strategy

- client.id

- zookeeper.session.timeout.ms

- zookeeper.connection.timeout.ms

- zookeeper.sync.time.ms

- offsets.storage

- offsets.channel.backoff.ms

- offsets.channel.socket.timeout.ms

- offsets.commit.max.retries

- dual.commit.enabled

- partition.assignment.strategy

- 3.3. Producer Configs

- metadata.broker.list

- request.required.acks

- request.timeout.ms

- producer.type

- serializer.class

- key.serializer.class

- partitioner.class

- compression.codec

- compressed.topics

- message.send.max.retries

- retry.backoff.ms

- topic.metadata.refresh.interval.ms

- queue.buffering.max.ms

- queue.buffering.max.messages

- queue.enqueue.timeout.ms

- batch.num.messages

- send.buffer.bytes

- client.id

- 3.4. New Producer Configs

- bootstrap.servers

- acks

- buffer.memory

- compression.type

- retries

- batch.size

- client.id

- linger.ms

- max.request.size

- receive.buffer.bytes

- send.buffer.bytes

- timeout.ms

- block.on.buffer.full

- metadata.fetch.timeout.ms

- metadata.max.age.ms

- metric.reporters

- metrics.num.samples

- metrics.sample.window.ms

- reconnect.backoff.ms

- retry.backoff.ms

- 3.1. ブローカ設定

- 4. 設計

- 5. 実装

- 6. 運用

1 はじめよう

1.1 導入

▶ show original text

Getting Started

Introduction

Kafka is a distributed, partitioned, replicated commit log service. It provides the functionality of a messaging system, but with a unique design.

Kafka は分散し、分割され、複製されるコミットログサービスです。 メッセージングシステムの機能を提供しますが、その設計は独特なものです。

▶ show original text

What does all that mean?

つまり、どういうことでしょう?

▶ show original text

First let's review some basic messaging terminology:

- Kafka maintains feeds of messages in categories called topics.

- We'll call processes that publish messages to a Kafka topic producers.

- We'll call processes that subscribe to topics and process the feed of published messages consumers..

- Kafka is run as a cluster comprised of one or more servers each of which is called a broker.

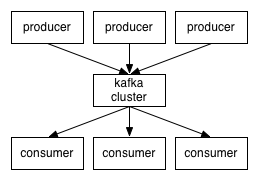

So, at a high level, producers send messages over the network to the Kafka cluster which in turn serves them up to consumers like this:

はじめに、基本的なメッセージングの用語を確認しておきましょう:

- Kafka は トピック と呼ばれるカテゴリ毎にメッセージのフィードを保持しています

- Kafka のトピックに対してメッセージを発行するプロセスを プロデューサ と呼びます

- 複数のトピックを購読し、発行されたメッセージのフィードを処理するプロセスを コンシューマ と呼びます

- Kafka はひとつ以上の ブローカ と呼ばれるサーバで構成されるクラスタとして動作します

すなわち以下の図のように、高レベルな視点ではプロデューサ群がネットワーク上で Kafka クラスタにメッセージを送信し、 そのメッセージを順次コンシューマ群に向けて提供する、というように動作します:

▶ show original text

Communication between the clients and the servers is done with a simple, high-performance, language agnostic TCP protocol. We provide a Java client for Kafka, but clients are available in many languages.

クライアントとサーバ間の通信はシンプルかつ高性能で、言語に依存しない TCP protocol で行なわれます。 提供されるのは Java の Kafka クライアントですが、 多くの言語で 利用することが出来ます。

トピックとログ

▶ show original text

Topics and Logs

Let's first dive into the high-level abstraction Kafka provides—the topic.

まず最初に、 Kafka が提供する高レベルな抽象概念である「トピック」について見ていきましょう。

▶ show original text

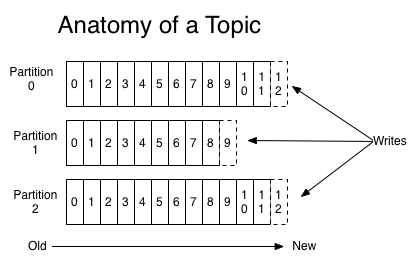

A topic is a category or feed name to which messages are published. For each topic, the Kafka cluster maintains a partitioned log that looks like this:

トピックはカテゴリ、あるいはフィードの名前であり、メッセージはトピックに対して発行されます。 以下の図のように、Kafka クラスタはトピックごとにログを分割して保持しています:

▶ show original text

Each partition is an ordered, immutable sequence of messages that is continually appended to—a commit log. The messages in the partitions are each assigned a sequential id number called the offset that uniquely identifies each message within the partition.

各パーティションは不変で順序があるメッセージ列で、メッセージは断続的に追記されます。 このメッセージ列を「コミットログ」と呼びます。 メッセージには、格納されたパーティションごとに「オフセット」と呼ばれるユニークな通し番号が付与されます。 このオフセットにより、パーティション内のメッセージを一意に特定することができます。

▶ show original text

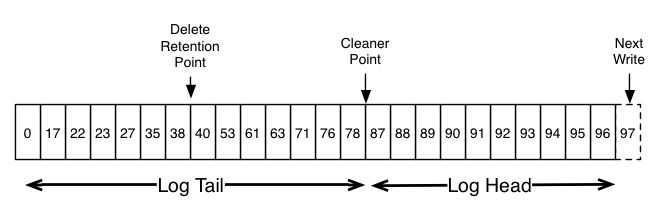

The Kafka cluster retains all published messages—whether or not they have been consumed—for a configurable period of time. For example if the log retention is set to two days, then for the two days after a message is published it is available for consumption, after which it will be discarded to free up space. Kafka's performance is effectively constant with respect to data size so retaining lots of data is not a problem.

Kafka クラスタは、コンシュームされたかどうかに拘わらず、発行されたすべてのメッセージを保存しています。 保持する期間は設定で変更可能です。 例えばログ保存期間が2日間に設定されている場合、あるメッセージが発行されてから2日間はコンシューム可能ですが、 それ以降は容量確保のために破棄されます。 Kafkaの性能はデータサイズに関しては実質定数のため、大量のデータを保存することは問題ありません。

▶ show original text

In fact the only metadata retained on a per-consumer basis is the position of the consumer in the log, called the "offset". This offset is controlled by the consumer: normally a consumer will advance its offset linearly as it reads messages, but in fact the position is controlled by the consumer and it can consume messages in any order it likes. For example a consumer can reset to an older offset to reprocess.

実は、コンシューマ毎に保存されているメタデータというのは、ログ内のコンシューマの位置情報だけです。 これは「オフセット」と呼ばれます。 オフセットはコンシューマにより制御されます————通常はメッセージを読み進めるのに応じて順番にオフセットを進めますが、 オフセットの制御は実際のところコンシューマが行なうため、任意の順序でコンシュームすることが出来ます。 例えば、コンシューマは昔のオフセットにリセットして再処理を行なうことが出来ます。

▶ show original text

This combination of features means that Kafka consumers are very cheap—they can come and go without much impact on the cluster or on other consumers. For example, you can use our command line tools to "tail" the contents of any topic without changing what is consumed by any existing consumers.

以上の機能の組合せにより、Kafkaのコンシューマはとても安価であると言えます————コンシューマはクラスタへの参加・離脱を、 そのクラスタや、クラスタに所属する他のコンシューマに大きな影響を与えることなく行なうことができる、ということです。 例えば、任意のトピックについて、付属のコマンドラインツールで「tail」操作を行なうことが出来ますが、 これは既存のコンシューマのコンシューム状況を変えることなく行なうことが可能です。

▶ show original text

The partitions in the log serve several purposes. First, they allow the log to scale beyond a size that will fit on a single server. Each individual partition must fit on the servers that host it, but a topic may have many partitions so it can handle an arbitrary amount of data. Second they act as the unit of parallelism—more on that in a bit.

パーティションは様々な目的で提供されています。 第一に、ログを一台のサーバに収まりきらないサイズにまでスケールすることを可能にする目的です。 個々のパーティションについては、それを格納するサーバに収まるように調整する必要がありますが、 トピックは複数のパーティションに分割されるため、トピックのデータ量は無制限です。 第二に、パーティションは並行処理の単位としても利用されます————詳細は後述します。

分散

▶ show original text

Distribution The partitions of the log are distributed over the servers in the Kafka cluster with each server handling data and requests for a share of the partitions. Each partition is replicated across a configurable number of servers for fault tolerance.

ログのパーティションは Kafka クラスタ内のサーバ上で分散して保持されており、 各サーバはパーティションを共有するためのデータとリクエストを処理します。 耐障害性のために、各パーティションを複数のサーバに複製することも出来ます。 複製するサーバ数は設定で変更可能です。

▶ show original text

Each partition has one server which acts as the "leader" and zero or more servers which act as "followers". The leader handles all read and write requests for the partition while the followers passively replicate the leader. If the leader fails, one of the followers will automatically become the new leader. Each server acts as a leader for some of its partitions and a follower for others so load is well balanced within the cluster.

各パーティションは「リーダ」となる一つのサーバと、0以上の「フォロワ」サーバを持ちます。 リーダは担当のパーティションへの全ての読み書きリクエストを処理します。 対してフォロワは、リーダの複製を受動的に行ないます。 リーダに障害が発生した場合、フォロワのどれかが自動的に新たなリーダとなります。 各サーバはクラスタ内の負荷が均等になるように、自身のパーティションのうちいくつかのリーダとなり、 その他のパーティションのフォロワともなります。

プロデューサ

▶ show original text

Producers

Producers publish data to the topics of their choice. The producer is responsible for choosing which message to assign to which partition within the topic. This can be done in a round-robin fashion simply to balance load or it can be done according to some semantic partition function (say based on some key in the message). More on the use of partitioning in a second.

プロデューサは自身の選択したトピックに対してデータを発行します。 プロデューサはどのメッセージをトピック内のどのパーティションに割り当てるかを選択する責務があります。 これは負荷分散のためにラウンドロビン方式で選択することも出来ますし、 何らかの意味的な分割関数を利用することも出来ます(例えばメッセージの特定のキーを元に分割するなど)。 パーティションの利用に関する詳細は後述します。

コンシューマ

▶ show original text

Messaging traditionally has two models: queuing and publish-subscribe. In a queue, a pool of consumers may read from a server and each message goes to one of them; in publish-subscribe the message is broadcast to all consumers. Kafka offers a single consumer abstraction that generalizes both of these—the consumer group.

伝統的なメッセージングのモデルは キューイング と 出版・購読型 の二つです。 キューを用いる方法では、コンシューマプールがひとつのサーバからメッセージを取得することができ、 各メッセージはコンシューマのいずれか一つに渡ります。 一方の出版・購読型モデルでは、メッセージは全てのコンシューマにブロードキャストされます。 Kafka はその両方を一般化するコンシューマの抽象概念を提供しています。 それが「コンシューマグループ」です。

▶ show original text

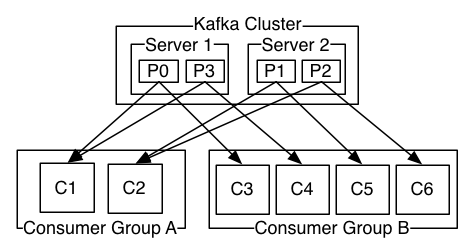

Consumers label themselves with a consumer group name, and each message published to a topic is delivered to one consumer instance within each subscribing consumer group. Consumer instances can be in separate processes or on separate machines.

コンシューマは自分自身にコンシューマグループ名をラベル付けしており、 トピックに発行される各メッセージは、そのトピックを購読している各コンシューマグループそれぞれの、 ある一つのコンシューマインスタンスに対して屆けられます。 コンシューマインスタンスは異なるプロセス、あるいは異なるサーバ上で稼動させることが出来ます。

▶ show original text

If all the consumer instances have the same consumer group, then this works just like a traditional queue balancing load over the consumers.

全てのコンシューマインスタンスが同一のコンシューマグループに属しているならば、 コンシューマ上で負荷分散される伝統的なキューイングモデルのように動きます。

▶ show original text

If all the consumer instances have different consumer groups, then this works like publish-subscribe and all messages are broadcast to all consumers.

全てのコンシューマインスタンスがそれぞれ異なるコンシューマグループに属しているならば、 出版・購読型モデルのように動き、メッセージは全てのコンシューマにブロードキャストされることになります。

▶ show original text

More commonly, however, we have found that topics have a small number of consumer groups, one for each "logical subscriber". Each group is composed of many consumer instances for scalability and fault tolerance. This is nothing more than publish-subscribe semantics where the subscriber is cluster of consumers instead of a single process.

しかしより一般には、トピックは「論理的な購読者」を表す少数のコンシューマグループを持つことになるでしょう。 各グループはスケーラビリティと耐障害性のため、複数のコンシューマインスタンスで構成されます。 これは購読者が単一のプロセスではなく、コンシューマのクラスタとなっている出版・購読型モデルそのものです。

Figure 3: 4つのパーティション(P0-P3)をホスティングする2つのサーバで構成されるKafka クラスタ、及び2つのコンシューマグループ。グループAは2つ、Bは4つのインスタンスを持っている。

▶ show original text

Caption: A two server Kafka cluster hosting four partitions (P0-P3) with two consumer groups. Consumer group A has two consumer instances and group B has four.

Kafka has stronger ordering guarantees than a traditional messaging system, too.

また、Kafkaは伝統的なメッセージングシステムと比べてより強力な順序保証を提供しています。

▶ show original text

A traditional queue retains messages in-order on the server, and if multiple consumers consume from the queue then the server hands out messages in the order they are stored. However, although the server hands out messages in order, the messages are delivered asynchronously to consumers, so they may arrive out of order on different consumers. This effectively means the ordering of the messages is lost in the presence of parallel consumption. Messaging systems often work around this by having a notion of "exclusive consumer" that allows only one process to consume from a queue, but of course this means that there is no parallelism in processing.

伝統的なキューはメッセージを順番にサーバ上に保存しています。 複数のコンシューマがそのキューからコンシュームした場合、 サーバは保存されている順番にメッセージを取り出すでしょう。 しかし、サーバがメッセージを順番に取り出したところで、 コンシューマへのメッセージの配信は非同期に行われるため、 異なるコンシューマ間のメッセージ到達順序は狂う可能性があります。 つまり、コンシューマを並列に動かすような状況では、メッセージの順序は失われる、ということです。 メッセージングシステムはしばしば「排他的コンシューマ」という概念を利用して問題を回避しようとします。 ひとつのキューに対してただひとつプロセスのみコンシューム可能とする、というものです。 しかしこれは当然、並列処理は出来ません。

▶ show original text

Kafka does it better. By having a notion of parallelism—the partition—within the topics, Kafka is able to provide both ordering guarantees and load balancing over a pool of consumer processes. This is achieved by assigning the partitions in the topic to the consumers in the consumer group so that each partition is consumed by exactly one consumer in the group. By doing this we ensure that the consumer is the only reader of that partition and consumes the data in order. Since there are many partitions this still balances the load over many consumer instances. Note however that there cannot be more consumer instances than partitions.

Kafka はもっと上手いことやっています。 トピック内の並列性(これはつまり、パーティションのことです)という概念を利用することで、 Kafkaはコンシューマプロセスプール上の順序保証と負荷分散の両方を提供することが出来ます。 これは、各パーティションがグループ内のただ一つのコンシューマにのみコンシュームされるように、 トピック内のパーティションをコンシューマグループ内のコンシューマに割り当てることで実現されています。 これによって、パーティションを読むのはある特定コンシューマだけであることと、順序通りコンシュームすることが保証されます。 多くのパーティションがある為、これでもコンシューマインスタンス間の負荷は分散します。 ただし、パーティション数以上のコンシューマインスタンスは存在し得ないことに注意してください。

▶ show original text

Kafka only provides a total order over messages within a partition, not between different partitions in a topic. Per-partition ordering combined with the ability to partition data by key is sufficient for most applications. However, if you require a total order over messages this can be achieved with a topic that has only one partition, though this will mean only one consumer process.

Kafka はトピック内のパーティションの 中の メッセージ順序しか保証しません。 異なるパーティション間の順序は保証されません。 ほとんどのアプリケーションは、パーティション毎の順序とキー毎の分割機能との組み合わせで十分でしょう。 もし、全メッセージの順序が必要な場合は、パーティションひとつだけからなるトピックを使うことで実現出来ますが、 この場合コンシューマプロセスもただ一つのみになります。

保証

▶ show original text

Guarantees

At a high-level Kafka gives the following guarantees:

- Messages sent by a producer to a particular topic partition will be appended in the order they are sent. That is, if a message M1 is sent by the same producer as a message M2, and M1 is sent first, then M1 will have a lower offset than M2 and appear earlier in the log.

- A consumer instance sees messages in the order they are stored in the log.

- For a topic with replication factor N, we will tolerate up to N-1 server failures without losing any messages committed to the log.

More details on these guarantees are given in the design section of the documentation.

高レベルな視点では Kafka は以下の保証を提供します:

- プロデューサから特定のトピックパーティションへと送られたメッセージは、送られた順に追記されます。

つまり、メッセージ

M1とM2が同じプロデューサから送られ、かつM1が最初に送られていた場合、M1はM2よりも小さいオフセットを持ち、M2よりも先にログに現れます。 - コンシューマインスタンスはログに保存されている順番にメッセージを読みます。

- レプリケーションファクタ

Nに設定されたトピックは、N-1個までのサーバ障害については、 メッセージのロスト無く稼動することが出来ます。

これらの保証のより詳細については、本ドキュメントの設計セクションで述べられています。

1.2 ユースケース

▶ show original text

Use Cases

Here is a description of a few of the popular use cases for Apache Kafka. For an overview of a number of these areas in action, see this blog post.

Apache Kafka のユースケースをいくつか紹介します。 これらの分野についての数多くの取り組みの概要が このブログ記事 にまとめられています。

メッセージング

▶ show original text

Messaging

Kafka works well as a replacement for a more traditional message broker. Message brokers are used for a variety of reasons (to decouple processing from data producers, to buffer unprocessed messages, etc). In comparison to most messaging systems Kafka has better throughput, built-in partitioning, replication, and fault-tolerance which makes it a good solution for large scale message processing applications.

Kafka は伝統的なメッセージブローカの代替として使うことが出来ます。 メッセージブローカを利用する理由は様々です—— データ生成と処理を疎結合にする為、未処理のメッセージをバッファするため、等。 ほとんどのメッセージングシステムと比較して、 Kafka はより良いスループット、組込みのパーティショニング、複製、耐障害性を備えており、 大規模メッセージ処理アプリケーションの良いソリューションとなります。

▶ show original text

In our experience messaging uses are often comparatively low-throughput, but may require low end-to-end latency and often depend on the strong durability guarantees Kafka provides.

経験上、メッセージングは比較的低いスループットで、しかしエンドツーエンドの低いレイテンシを要求し、 また、Kafka が提供する強い堅牢性に関する保証に依存するという場合が多いです。

▶ show original text

このドメインでは、 ActiveMQ や RabbitMQ のような伝統的なメッセージングシステムと Kafka を比較することが出来ます。

Web サイトのアクティビティトラッキング

▶ show original text

Website Activity Tracking

The original use case for Kafka was to be able to rebuild a user activity tracking pipeline as a set of real-time publish-subscribe feeds. This means site activity (page views, searches, or other actions users may take) is published to central topics with one topic per activity type. These feeds are available for subscription for a range of use cases including real-time processing, real-time monitoring, and loading into Hadoop or offline data warehousing systems for offline processing and reporting.

ユーザ動向追跡パイプラインを、リアルタイムな Pub-Sub フィードの集合として再構築する、というのが Kafka の元々のユースケースでした。 つまり、サイトアクティビティ(ページビュー、検索等のユーザが取り得る行動)はアクティビティの種別毎にトピック分けされて、 中央に集められるということです。 これらのフィードは幅広いユースケースで利用することが出来ます。 リアルタイム処理やリアルタイム監視のために使われたり、 オフラインでの処理やレポートで利用するために Hadoop やオフラインのデータウェアハウジングシステムへ保存するために使われたりします。

▶ show original text

Activity tracking is often very high volume as many activity messages are generated for each user page view.

アクティビティトラッキングは各ユーザのページビューごとに大量のアクティビティメッセージが生成されるため、 しばしば超大容量のログを扱うことになります。

メトリクス

▶ show original text

Metrics

Kafka is often used for operational monitoring data. This involves aggregating statistics from distributed applications to produce centralized feeds of operational data.

Kafka は運用監視データとしても使われることがあります。 この場合は、運用データの中央フィードを生成するため、分散したアプリケーションの統計を集約するのに用いられます。

ログ集約

▶ show original text

Log Aggregation

Many people use Kafka as a replacement for a log aggregation solution. Log aggregation typically collects physical log files off servers and puts them in a central place (a file server or HDFS perhaps) for processing. Kafka abstracts away the details of files and gives a cleaner abstraction of log or event data as a stream of messages. This allows for lower-latency processing and easier support for multiple data sources and distributed data consumption. In comparison to log-centric systems like Scribe or Flume, Kafka offers equally good performance, stronger durability guarantees due to replication, and much lower end-to-end latency.

ログ集約ソリューションの代替として Kafka を利用する場合も多いです。 典型的なログ集約では、物理ログファイルをサーバから収集し、 ファイルサーバや HDFS のような中央ストレージに配置して処理されます。 Kafka はファイルの詳細について抽象化し、 また、ログやイベントデータをメッセージストリームとしてきれいに抽象化しています。 これにより、より低レイテンシで処理でき、また複数のデータソースや分散データ処理への対応が容易になります。 Scribe や Flume といったログ集約システムと比較して、 Kafka や同等のパフォーマンスと、複製によるより強い堅牢性保証、 及びエンドツーエンドのより低いレイテンシを提供します。

ストリーム処理

▶ show original text

Stream Processing Many users end up doing stage-wise processing of data where data is consumed from topics of raw data and then aggregated, enriched, or otherwise transformed into new Kafka topics for further consumption. For example a processing flow for article recommendation might crawl article content from RSS feeds and publish it to an "articles" topic; further processing might help normalize or deduplicate this content to a topic of cleaned article content; a final stage might attempt to match this content to users. This creates a graph of real-time data flow out of the individual topics. Storm and Samza are popular frameworks for implementing these kinds of transformations.

多くのユーザは段階的なデータ処理をすることになります。 データは生データのトピックからコンシュームされ、集約され、肉付けされ、 あるいはさらなるコンシュームの為に新たな Kafka トピックへの変換されます。 例えば記事レコメンドの処理フローは次のようなものになるでしょう: まず、RSS フィードから記事をクロールし、「記事」トピックに発行します。 続いて、内容を正規化したり重複を除いて、「クリーンな記事内容」トピックに発行します。 最後に、記事内容とユーザのマッチングを行ないます。 このような処理のフローは、個々のトピックから始まるリアルタイムデータフローのグラフを形成します。 Storm や Samza はこのような類の変換を行なうための有名なフレームワークです。

イベントソーシング

▶ show original text

Event Sourcing

Event sourcing is a style of application design where state changes are logged as a time-ordered sequence of records. Kafka's support for very large stored log data makes it an excellent backend for an application built in this style.

イベントソーシング はアプリケーション設計手法のひとつで、 状態の変更が時系列順のレコード列として記録されるというものです。 Kafka は超巨大なログデータを扱えるため、 この手法で構築されたアプリケーションの優れたバックエンドとして利用することが出来ます。

コミットログ

▶ show original text

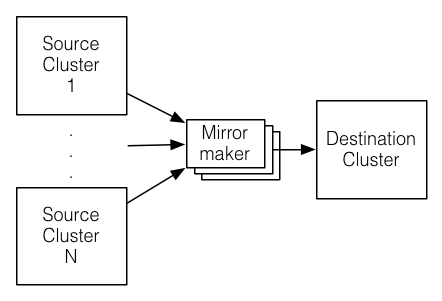

Commit Log Kafka can serve as a kind of external commit-log for a distributed system. The log helps replicate data between nodes and acts as a re-syncing mechanism for failed nodes to restore their data. The log compaction feature in Kafka helps support this usage. In this usage Kafka is similar to Apache BookKeeper project.

Kafka を分散システムのための外部コミットログとして使うこともできます。 ノード間でデータを複製したり、障害ノードの復旧のための再同期機構として、このログを利用することが出来ます。 Kafka の ログコンパクション 機能もこの用途に適しています。 この用途では、Kafka と Apache BookKeeper プロジェクトは似ています。

1.3 クイックスタート

▶ show original text

This tutorial assumes you are starting fresh and have no existing Kafka or ZooKeeper data.

このチュートリアルは、まっさらな環境で、KafkaやZooKeeperが一切稼動していない前提で進めます。

ステップ 1: コードのダウンロード

ステップ 2: サーバの起動

▶ show original text

Step 2: Start the server

Kafka uses ZooKeeper so you need to first start a ZooKeeper server if you don't already have one. You can use the convenience script packaged with kafka to get a quick-and-dirty single-node ZooKeeper instance.

Kafka は ZooKeeper を使うため、まずは ZooKeeper サーバを起動する必要があります。 既に起動している ZooKeeper サーバがある場合は、新たに起動する必要はありません。 新たに起動する場合は、 Kafka に同梱されている便利スクリプトを使ってください。 このスクリプトは、単一ノードを手早く作るための適当なものです。

> bin/zookeeper-server-start.sh config/zookeeper.properties [2013-04-22 15:01:37,495] INFO Reading configuration from: config/zookeeper.properties (org.apache.zookeeper.server.quorum.QuorumPeerConfig) ...

▶ show original text

Now start the Kafka server:

では、 Kafka サーバを起動しましょう:

> bin/kafka-server-start.sh config/server.properties [2013-04-22 15:01:47,028] INFO Verifying properties (kafka.utils.VerifiableProperties) [2013-04-22 15:01:47,051] INFO Property socket.send.buffer.bytes is overridden to 1048576 (kafka.utils.VerifiableProperties) ...

ステップ 3: トピックの作成

▶ show original text

Step 3: Create a topic

Let's create a topic named "test" with a single partition and only one replica:

今度は「test」という名前の、単一パーティションで、複製を作らないトピックを作成してみましょう:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --create --zookeeper localhost:2181 --replication-factor 1 --partitions 1 --topic test

▶ show original text

We can now see that topic if we run the list topic command:

list コマンドで、作成したトピックを参照できるようになるはずです:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --list --zookeeper localhost:2181 test

▶ show original text

Alternatively, instead of manually creating topics you can also configure your brokers to auto-create topics when a non-existent topic is published to.

また、手動でトピックを作成するのではなく、存在しないトピックへパブリッシュされた場合に自動で作成するようにブローカを設定することもできます。

ステップ 4: メッセージを送ってみる

▶ show original text

Step 4: Send some messages

Kafka comes with a command line client that will take input from a file or from standard input and send it out as messages to the Kafka cluster. By default each line will be sent as a separate message.

Kafka にはファイルか標準入力から Kafka クラスタにメッセージを送信出来るコマンドラインのクライアントが同梱されています。 デフォルトでは、各行がそれぞれ異なるメッセージとして送信されます。

▶ show original text

Run the producer and then type a few messages into the console to send to the server.

プロデューサスクリプトを起動し、コンソールにメッセージを打ちこんでサーバに送信してみましょう。 1

> bin/kafka-console-producer.sh --broker-list localhost:9092 --topic test [2015-05-15 19:45:39,512] WARN Property topic is not valid (kafka.utils.VerifiableProperties) これはメッセージです これは別のメッセージです ^D

ステップ 5: コンシューマを起動する

▶ show original text

Kafka also has a command line consumer that will dump out messages to standard output.

Kafka にはメッセージを標準出力にダンプするコマンドラインのコンシューマも付属しています。

> bin/kafka-console-consumer.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --topic test --from-beginning これはメッセージです これも別のメッセージです ^CConsumed 2 messages

▶ show original text

If you have each of the above commands running in a different terminal then you should now be able to type messages into the producer terminal and see them appear in the consumer terminal.

別々のターミナルで上記の両方のコマンドを実行すれば、プロデューサのターミナルでメッセージを打ち込むと、 コンシューマのターミナルでそれを確認することが出来ます。

▶ show original text

All of the command line tools have additional options; running the command with no arguments will display usage information documenting them in more detail.

全てのコマンドラインツールには追加のオプションがあります。 引数なしでコマンドを実行すると、より詳細が参照出来る使い方のドキュメントが出力されます。

ステップ 6: マルチブローカクラスタを立ち上げる

▶ show original text

Step 6: Setting up a multi-broker cluster

So far we have been running against a single broker, but that's no fun. For Kafka, a single broker is just a cluster of size one, so nothing much changes other than starting a few more broker instances. But just to get feel for it, let's expand our cluster to three nodes (still all on our local machine).

ここまでは、単一のブローカ上で動作させて決ましたが、これではあまり面白くないですね。 単一のブローカというのは Kafka にとってはサイズ1のクラスタに過ぎないので、 複数のブローカインスタンスを起動することもそれほど違いはありません。 ですが、感覚を掴む為に3ノードのクラスタに拡張してみましょう(とはいえ、まだ全てのノードは同じローカルマシン上です)。

▶ show original text

First we make a config file for each of the brokers:

まず、各ブローカ用の設定ファイルを作ります:

> cp config/server.properties config/server-1.properties > cp config/server.properties config/server-2.properties

▶ show original text

Now edit these new files and set the following properties:

続いて、これらのファイルを編集して、以下のプロパティを設定します:

config/server-1.properties:

broker.id=1

port=9093

log.dirs=/tmp/kafka-logs-1

config/server-2.properties:

broker.id=2

port=9094

log.dirs=/tmp/kafka-logs-2

▶ show original text

The broker.id property is the unique and permanent name of each node in the cluster. We have to override the port and log directory only because we are running these all on the same machine and we want to keep the brokers from all trying to register on the same port or overwrite each others data.

broker.id は、各ノードのクラスタ内でユニークな、永続的な名前を表すプロパティです。

ポート番号とログディレクトリだけは変更が必要です。

いま、これらのブローカは全て同一のマシン上で稼動しているので、

同じポート番号に登録しようとしたり、お互いのデータを上書きしあったりしてしまわないようにする必要があるためです。

▶ show original text

We already have Zookeeper and our single node started, so we just need to start the two new nodes:

既に ZooKeeper と単一ノードは起動しているので、3ノードのクラスタにするには、新しく2つのノードを立ち上げるだけです:

> bin/kafka-server-start.sh config/server-1.properties > /dev/null 2>&1 & ... > bin/kafka-server-start.sh config/server-2.properties > /dev/null 2>&1 & ...

▶ show original text

Now create a new topic with a replication factor of three:

では、レプリケーションファクタ3のトピックを作成してみます:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --create --zookeeper localhost:2181 --replication-factor 3 --partitions 1 --topic my-replicated-topic

▶ show original text

Okay but now that we have a cluster how can we know which broker is doing what? To see that run the "describe topics" command:

出来ました、が、クラスタ上のブローカの状態を見るにはどうすればよいのでしょう? その為には "describe topics" コマンドを実行します:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --describe --zookeeper localhost:2181 --topic my-replicated-topic Topic:my-replicated-topic PartitionCount:1 ReplicationFactor:3 Configs: Topic: my-replicated-topic Partition: 0 Leader: 1 Replicas: 1,2,0 Isr: 1,2,0

▶ show original text

Here is an explanation of output. The first line gives a summary of all the partitions, each additional line gives information about one partition. Since we have only one partition for this topic there is only one line.

出力内容の説明をします。 最初の行が全パーティションの要約で、続く各行がそれぞれ1パーティションの情報を表します。 このトピックにはパーティションが一つしかないので、出力は1行しかありません。

▶ show original text

- "leader" is the node responsible for all reads and writes for the given partition. Each node will be the leader for a randomly selected portion of the partitions.

- "replicas" is the list of nodes that replicate the log for this partition regardless of whether they are the leader or even if they are currently alive.

- "isr" is the set of "in-sync" replicas. This is the subset of the replicas list that is currently alive and caught-up to the leader.

Leaderはそのパーティションの全読み書きの責務を負うノードです。各ノードは、ランダムに選択されたパーティションのリーダになり得ますReplicasはこのパーティションのログを複製しているノードのリストです。リーダか否か、現在生存しているノードかどうかにはかかわらず表示されますIsrは「同期中」の複製を表します。Replicasのリストのうち、現在生存しており、リーダに追い付いているノードが表示されます

▶ show original text

Note that in my example node 1 is the leader for the only partition of the topic.

この例では、ノード1はこのトピックの唯一のパーティションのリーダであることに着目してください。

▶ show original text

We can run the same command on the original topic we created to see where it is:

同じコマンドを最初に作ったトピックについて実行して、ブローカの状況を見てみましょう:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --describe --zookeeper localhost:2181 --topic test Topic:test PartitionCount:1 ReplicationFactor:1 Configs: Topic: test Partition: 0 Leader: 0 Replicas: 0 Isr: 0

▶ show original text

So there is no surprise there—the original topic has no replicas and is on server 0, the only server in our cluster when we created it.

特に変わったところはありません——このトピックは複製を一切持たず、元々クラスタを作成したときの唯一のノードである server 0 上にあります。

▶ show original text

Let's publish a few messages to our new topic:

さて、新しく作った方のトピックにいくつかメッセージをパブリッシュしてみましょう:

> bin/kafka-console-producer.sh --broker-list localhost:9092 --topic my-replicated-topic ... my test message 1 my test message 2 ^D

▶ show original text

Now let's consume these messages:

続いてこれらのメッセージをコンシュームします:

> bin/kafka-console-consumer.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --from-beginning --topic my-replicated-topic ... my test message 1 my test message 2 ^C

▶ show original text

Now let's test out fault-tolerance. Broker 1 was acting as the leader so let's kill it:

ここで、耐障害性のテストをしてみましょう。 今はブローカ1がリーダなので、こいつを殺しましょう:

> ps | grep server-1.properties 7564 ttys002 0:15.91 /System/Library/Frameworks/JavaVM.framework/Versions/1.6/Home/bin/java... > kill -9 7564

▶ show original text

Leadership has switched to one of the slaves and node 1 is no longer in the in-sync replica set:

リーダシップがスレーブノードの1つに移され、ノード1は Isr から外れます:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --describe --zookeeper localhost:2181 --topic my-replicated-topic Topic:my-replicated-topic PartitionCount:1 ReplicationFactor:3 Configs: Topic: my-replicated-topic Partition: 0 Leader: 2 Replicas: 1,2,0 Isr: 2,0

▶ show original text

But the messages are still be available for consumption even though the leader that took the writes originally is down:

元々の書き込みを引き受けたリーダがダウンしているにもかかわらず、なおメッセージはコンシューム可能です。

> bin/kafka-console-consumer.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --from-beginning --topic my-replicated-topic ... my test message 1 my test message 2 ^C

1.4 エコシステム

▶ show original text

Ecosystem

There are a plethora of tools that integrate with Kafka outside the main distribution. The ecosystem page lists many of these, including stream processing systems, Hadoop integration, monitoring, and deployment tools.

メインディストリビューション外にも、Kafka 関連のツールが大量にあります。 エコシステムのページ に、ストリームプロセッシングシステムやHadoopとの統合、モニタリング、デプロイ等、 それらのツールの多くが列挙されています。

1.5 以前のバージョンからのアップグレード

▶ show original text

Upgrading From Previous Versions

0.8.1 から 0.8.2.0 へのアップグレード

▶ show original text

Upgrading from 0.8.1 to 0.8.2.0

0.8.2.0 is fully compatible with 0.8.1. The upgrade can be done one broker at a time by simply bringing it down, updating the code, and restarting it.

0.8.2.0 は 0.8.1 と完全に互換性があります。 単純に1台ずつブローカ停止し、コードを更新し、再起動することでアップグレード出来ます。

0.8.0 から 0.8.1 へのアップグレード

▶ show original text

Upgrading from 0.8.0 to 0.8.1

0.8.1 is fully compatible with 0.8. The upgrade can be done one broker at a time by simply bringing it down, updating the code, and restarting it.

0.8.1 は 0.8 と完全に互換性があります。 単純に1台ずつブローカ停止し、コードを更新し、再起動することでアップグレード出来ます。

0.7 からのアップグレード

▶ show original text

Upgrading from 0.7

0.8, the release in which added replication, was our first backwards-incompatible release: major changes were made to the API, ZooKeeper data structures, and protocol, and configuration. The upgrade from 0.7 to 0.8.x requires a special tool for migration. This migration can be done without downtime.

レプリケーションが追加された 0.8 は、初めて後方互換性が失われたリリースでした。 API、 ZooKeeper のデータ構造、プロトコル、設定に主要な変更が入りました。 0.7 から 0.8.x へのアップグレードには、移行のための 特別なツール が必要です。 移行は無停止で行なうことが可能です。

2 API

現在 Kafka の JVM クライアントをリライト中です。 0.8.2 では、新規に書き直された Java プロデューサーが同梱されています。 次期リリースでは同様に Java コンシューマを含める予定です。 これらの新しいクライアントは既存の Scala クライアントを置き換えるものとなる見込みですが、 互換性のためにしばらくは共存することになります。 これらのクライアントは別のjarで提供され、最低限の依存関係だけが定義されています。 過去の Scala クライアントは、サーバと同じパッケージに同梱されていました。 2

2.1 プロデューサ API

0.8.2 では、新規開発には新しい Java プロデューサを使うことを強くお奨めします。 これは実稼動環境での試験が済んでおり、一般的に以前の Scala クライアントよりも高速で高機能です。 以下のように、クライアント jar への依存を maven の pom に指定することで利用できます:

<dependency> <groupId>org.apache.kafka</groupId> <artifactId>kafka-clients</artifactId> <version>0.8.2.0</version> </dependency>

使い方や使用例は javadoc に書かれています。

レガシーな Scala プロデューサ API についてもし興味があれば、 ここ を参照してください。

2.2 ハイレベルコンシューマ API

class Consumer { /** * ConsumerConnector の作成 * * @param config コンシューマの groupid と、 ZooKeeper との接続情報文字列 zookeeper.connect が、 * 最低限必要 */ public static kafka.javaapi.consumer.ConsumerConnector createJavaConsumerConnector(ConsumerConfig config); } /** * V: メッセージの型 * K: メッセージに関連付けられたオプショナルなキー */ public interface kafka.javaapi.consumer.ConsumerConnector { /** * トピック毎に <K,V> 型のメッセージストリームのリストを生成する。 * * @param topicCountMap (トピック, ストリーム数) の Map * @param keyDecoder バイト列の Message を K 型へ変換するデコーダ * @param valueDecoder バイト列の Message から V 型へ変換するデコーダ * @return (トピック, KafkaStream のリスト) の Map。 * リストの要素数はストリーム数となる。 * 各ストリームは (メッセージ, メタデータ) のペア (MessageAndMetadata) のイテレータをサポートする。 */ public <K,V> Map<String, List<KafkaStream<K,V>>> createMessageStreams(Map<String, Integer> topicCountMap, Decoder<K> keyDecoder, Decoder<V> valueDecoder); /** * デフォルトのデコーダでトピック毎のストリームのリストを作成する。 */ public Map<String, List<KafkaStream<byte[], byte[]>>> createMessageStreams(Map<String, Integer> topicCountMap); /** * ワイルドカードにマッチしたトピックのメッセージストリームのリストを作成する。 * * @param topicFilter どのトピックを購読するかを特定する TopicFilter * (ホワイトリスト方式かブラックリスト方式かを隠蔽している)。 * @param numStreams 返すメッセージストリームの数 * @param keyDecoder メッセージキーをデコードするデコーダ * @param valueDecoder メッセージ自身をデコードするデコーダ * @return KafkaStream のリスト。 * 各ストリームは MessageAndMetadata 要素のイテレータをサポートする。 */ public <K,V> List<KafkaStream<K,V>> createMessageStreamsByFilter(TopicFilter topicFilter, int numStreams, Decoder<K> keyDecoder, Decoder<V> valueDecoder); /** * デフォルトのデコーダでワイルドカードにマッチしたトピックのメッセージストリームのリストを作成する。 */ public List<KafkaStream<byte[], byte[]>> createMessageStreamsByFilter(TopicFilter topicFilter, int numStreams); /** * ワイルドカードにマッチしたトピックのメッセージストリームをデフォルトのデコーダで一つだけ作成する。 */ public List<KafkaStream<byte[], byte[]>> createMessageStreamsByFilter(TopicFilter topicFilter); /** * このコネクタで接続している全てのトピック/パーティションのオフセットをコミットする */ public void commitOffsets(); /** * コネクタをシャットダウンする */ public void shutdown(); }

ハイレベルコンシューマ API の使い方を習得するには、この例 を参照して下さい。

2.3 シンプルコンシューマ API

class kafka.javaapi.consumer.SimpleConsumer { /** * トピックからメッセージのセットを取得する。 * * @param 取得するトピック名、パーティション、開始バイトオフセット、最大バイトを指定するリクエスト * @return 取得したメッセージのセット */ public FetchResponse fetch(kafka.javaapi.FetchRequest request); /** * 複数トピックのメタデータを取得する。 * * @param 取得する versionId, clientId, topic のシーケンスを指定するリクエスト。 * @return リクエストされた各トピックのメタデータ。 */ public kafka.javaapi.TopicMetadataResponse send(kafka.javaapi.TopicMetadataRequest request); /** * 与えられた時刻より以前の(maxSize以下の)妥当なオフセットのリストを取得する。 */ public kafak.javaapi.OffsetResponse getOffsetsBefore(OffsetRequest request); /** * シンプルコンシューマをクローズする。 */ public void close(); }

ほとんどのアプリケーションはハイレベルコンシューマ API で十分でしょう。 ハイレベルコンシューマではまだ提供されていない機能を利用したいアプリケーションもあるかもしれません (例えば、 再起動時の初期オフセットを設定するなど)。 その場合は低レベルな SimpleConsumer Api を利用出来ます。 利用する際のロジックはより複雑になります。 こちら の例に従ってやってみてください。

2.4 Kafka Hadoop コンシューマ API

データを集約し Hadoop に保存する、水平スケールするソリューションを提供するというのは、基本的なユースケースでした。 このユースケースをサポートするため、 Kafka クラスタから並列にデータを取得する大量のマップタスクを起動させる、Hadoop ベースのコンシューマを提供しています。 これにより高速なプルペースの Hadoop データロードが実現できます (ごく少ない Kafka サーバだけでネットワーク帯域を完全に使い切ることが出来ていました)。

Hadoop コンシューマの使用方法は こちら です。

3 設定

Kafka は プロパティファイルフォーマット の key-value ペアで設定を行ないます。 これらの値はファイル、もしくはプログラム中で設定することが出来ます。

3.1 ブローカ設定

broker.id

| デフォルト |

各ブローカは非負整数の ID により一意に識別されます。 この ID はブローカの「名前」として使われ、 そのブローカが異なるホスト/ポートに移動した際にもコンシューマは混乱なく利用出来るようになります。

クラスタ内でユニークでありさえすれば任意の数値を設定できます。

log.dirs

| デフォルト | /tmp/kafka-logs |

Kafka のデータが保存される1つ以上のディレクトリです。 複数指定する際はカンマで区切って指定します。 新しく作られた各パーティションは、 その時点で保持しているパーティションが最も少ないディレクトリに配置されます。

port

| デフォルト | 9092 |

クライアントからの接続を受け付けるサーバのポート番号です。

zookeeper.connect

| デフォルト | null |

ZooKeeperとの接続情報を hostname:port という形式で文字列で指定します。

hostname 、 port はそれぞれ ZooKeeper クラスタに属するノードのホスト名とポート番号です。

hostname1:port1,hostname2:port2,hostname3:port3 のように複数のホストを指定することで、

ホストダウン時に他のZooKeeperノードへ接続出来るように出来ます。

ZooKeeper では "chroot" パスを追加することも出来、

これによってクラスタ内の全ての Kafka データが特定のパス以下に配置されるように設定出来ます。

こうすることで、異なる Kafka クラスタや他のアプリケーションを、同じ ZooKeeper クラスタ上に構築出来ます。

具体的には、 hostname1:port1,hostname2:port2,hostname3:port3/chroot/path のように指定することで、

全 Kafka クラスタのデータが /chroot/path 以下に配置されるように出来ます。

chroot を指定する場合、全コンシューマが同じ接続情報文字列を利用するようにしなければなりません。

message.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 1000000 |

サーバが受け取るメッセージの最大サイズです。 このプロパティは コンシューマが利用する最大取得サイズ設定 と同調して設定するよう注意しましょう。 さもなければ、乱暴なプロデューサがコンシューマが扱えない程のサイズのメッセージを パブリッシュすることが出来るようになってしまいます。

num.network.threads

| デフォルト | 3 |

サーバがネットワークリクエストを処理するのに使うネットワークスレッドの数です。 恐らく変更する必要はありません。

num.io.threads

| デフォルト | 8 |

サーバがリクエストを処理するために使う I/O スレッドの数です。 少なくとも利用するディスク数分は用意するべきです。

background.threads

| デフォルト | 10 |

ファイル削除のような様々なバックグラウンド処理を行なう為に使われるスレッドの数です。 変更する必要はないでしょう。

queued.max.requests

| デフォルト | 500 |

I/O スレッドが処理する為にキューに詰まれる最大リクエスト数で、 この数までキューに詰まれると、ネットワークスレッドは新規リクエストを読むのを止めます。

host.name

| デフォルト | null |

ブローカのホスト名です。 この値が設定されていれば、そのアドレスにだけバインドします。 設定されていなければ、全インタフェースにバインドします。 この情報は ZooKeeper にパブリッシュされクライアントから利用されます。

advertised.host.name

advertised.port

| デフォルト | null |

プロデューサやコンシューマ、そして他のブローカが接続するポート番号です。 サーバがバインドするポートと異なる場合のみ必要な設定です。

socket.send.buffer.bytes

| デフォルト | 100 * 1024 |

ソケット接続時にサーバが利用する SO_SNDBUFF バッファの値です。

socket.receive.buffer.bytes

| デフォルト | 100 * 1024 |

ソケット接続時にサーバが利用する SO_RCVBUFF バッファの値です。

socket.request.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 100 * 1024 * 1024 |

サーバが許容する最大リクエストサイズです。 メモリ不足に陥らないよう、 Java ヒープサイズよりも小さい値に設定すべきです。

num.partitions

| デフォルト | 1 |

トピック作成時に指定されなかった場合のデフォルトパーティション数です。

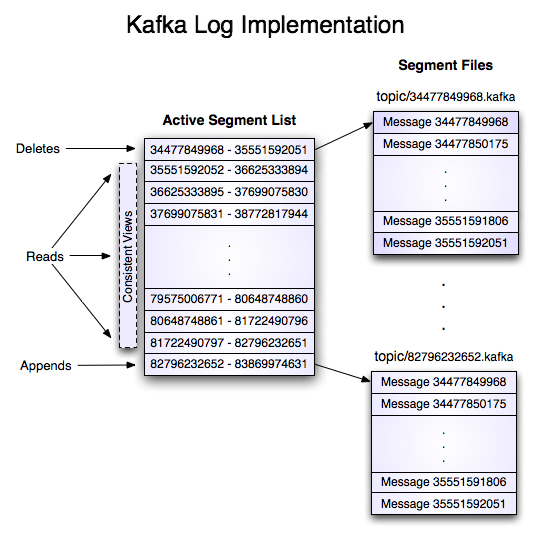

log.segment.bytes

| デフォルト | 1024 * 1024 * 1024 |

トピックパーティションのログは、セグメントファイルのディレクトリとして保存されています。 1セグメントのファイルサイズがこの値に達すると、新しいセグメントファイルが作成されます。 6 この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.roll.{ms,hours}

| デフォルト | 24 * 7 hours |

セグメントファイルサイズが log.segment.bytes に到達していない場合でも、

この設定値の時間が経過した場合に強制的に新たなログセグメントを作成するよう設定します。

この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

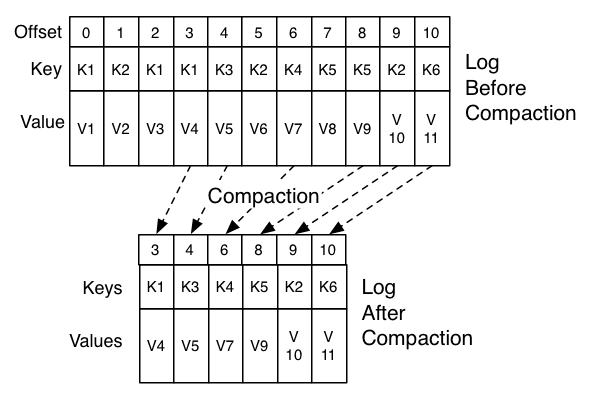

log.cleanup.policy

| デフォルト | delete |

delete または compact を設定出来ます。

ログセグメントがサイズや時間の上限に達した際に、

delete の場合は削除され、 compact の場合は ログコンパクション が行なわれます。

この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.retention.{ms,minutes,hours}

| デフォルト | 7 days |

ログセグメントを削除するまでの時間、つまりトピックのデフォルト保持期間です。

log.retention.minutes と log.retention.bytes が両方セットされていた場合、

いずれかの上限に達した時点でクリーンアップを行ないます。

この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.retention.bytes

| デフォルト | -1 |

各トピックパーティションログの総サイズ制限です。 これはパーティション毎の制限なので、トピックが必要とするトータルのデータ容量は、これにパーティション数を掛けた値になります。

log.retention.minutes と log.retention.bytes が両方セットされていた場合、

いずれかの上限に達した時点でクリーンアップを行ないます。

この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.retention.check.interval.ms

| デフォルト | 5 minutes |

ログの保持ポリシーと照らし合わせて、削除対象となるログセグメントがあるかどうかを確認する間隔です。

log.cleaner.enable

| デフォルト | false |

ログコンパクションを実行するためには、この設定は必ず true にしなければなりません。

log.cleaner.threads

| デフォルト | 1 |

ログコンパクション実行時のログクリーニングに使われるスレッド数です。

log.cleaner.io.max.bytes.per.second

| デフォルト | Double.MaxValue |

ログクリーナがログコンパクション実行時に発生する I/O の最大総サイズです。 この制限を設けることで、クリーナが運用中のサービスに影響を与えることを避けることが出来ます。

log.cleaner.dedupe.buffer.size

| デフォルト | 500*1024*1024 |

ログクリーナがクリーニング中にインデクシングとログの重複除去のために使用するバッファサイズです。 十分なメモリがあるならば、より大きな値の方が望ましいです。

log.cleaner.io.buffer.size

| デフォルト | 512*1024 |

ログクリーニング中に使用される I/O チャンクのサイズです。 恐らく変更する必要はないでしょう。

log.cleaner.io.buffer.load.factor

| デフォルト | 0.9 |

ログクリーニング中に使用されるハッシュテーブルの load factor です。 恐らく変更する必要はないでしょう。

log.cleaner.backoff.ms

| デフォルト | 15000 |

クリーニングが必要なログが無いか確認する間隔です。

log.cleaner.min.cleanable.ratio

| デフォルト | 0.5 |

ログコンパクション が有効なときの、ログコンパクタがログをクリーンする頻度を設定します。 デフォルトでは50%以上のログがコンパクションされていた場合はクリーニングを行ないません。 この比率はログの重複により無駄に使用される最大スペースを設定します (50%だと、多くて50%のログが重複している可能性がある、ということです)。 より高い比率に設定すれば、少ない回数で、より効率的なクリーニングが行われることになりますが、 それは同時にログが無駄に使用するスペースがより多くなるということにもなります。 この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.cleaner.delete.retention.ms

| デフォルト | 1 day |

ログコンパクション されたトピックの削除トゥームストーンマーカを保持する期間です。 最終段階の有効なスナップショットを確実に得る為にオフセット 0 から読み込みを開始する場合、 コンシューマはこの期間内に読み込みを完了させる必要があります (さもなければ、コンシューマの走査が完了する前に 削除トゥームストーンマーカが回収されてしまう可能性が有ります。)。 この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.index.size.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 10 * 1024 * 1024 |

各ログセグメントのオフセットインデックスが使用する容量の最大バイト数です。

ここで設定した容量のスパースファイルを事前に確保して、

新たなログセグメント作成のタイミングで実容量まで縮める、という動作をする点に注意してください。

インデックスがいっぱいになってしまった場合は、

log.segment.bytes を超過していない場合でも新たなログセグメントを作成します。

この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。

log.index.interval.bytes

| デフォルト | 4096 |

オフセットインデックスにエントリを追加するバイト間隔です。

取得リクエストを実行する際、サーバは取得を開始、あるいは終了するために、

正しいログ内の位置を見つけるため、ここで設定したバイト数まで線形走査する必要があります。

そのためこの値を大きくすればする程インデックスファイルは大きくなり

(そしてもう少しだけメモリを使用するようになり)ますが、走査回数は少なくなります。

7

ただ、サーバはログ追加毎に2つ以上インデックスエントリを追加することは決してありません

(たとえ log.index.interval を上回るメッセージが追加されたとしても)。

普通はこの値をいじる必要は無いでしょう。

log.flush.interval.messages

| デフォルト | Long.MaxValue |

ここで設定された数までメッセージをログパーティションに書き込んだら、強制的にログを fsync します。 この値を小さくすれば頻繁にディスクにデータを同期するようになりますが、パフォーマンスに多大な影響を与えます。 耐久性を得るためには、単一サーバの fsync に依存するよりもレプリケーションを利用することを通常は推奨しますが、 さらなる確実性を求める場合はこの設定を利用することも出来ます。

log.flush.scheduler.interval.ms

| デフォルト | Long.MaxValue |

ログフラッシャがディスクにフラッシュするのに適したログがあるかをチェックする頻度をミリ秒で設定します.

log.flush.interval.ms

| デフォルト | Long.MaxValue |

ログの fsync がコールされるまでの最大時間です。

log.flush.interval.messages と合わせて設定された場合は、

どちらかの条件を満たした時点でログがフラッシュされます。

log.delete.delay.ms

| デフォルト | 60000 |

メモリ上のセグメントインデックスから除去された後にログファイルを保持しておく期間です。 この期間はロックせずとも進行中の読み込みを中断することなく完了することが出来ます。 8 通常はこの値を変更する必要は無いでしょう。

log.flush.offset.checkpoint.interval.ms

| デフォルト | 60000 |

リカバリのためにログの最終フラッシュのチェックポイントをセットする頻度です。 これは変更すべきではありません。

log.segment.delete.delay.ms

| デフォルト | 60000 |

ファイルシステムからログセグメントファイルを削除するまでの時間です。

auto.create.topics.enable

| デフォルト | true |

サーバに自動でトピックを作成可能にします。 この設定が有効な場合、存在しないトピックを作成、あるいはそのメタデータを取得しようとした際に、 デフォルトのレプリケーションファクタとパーティション数で自動的にトピックが作成されます。

controller.socket.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 30000 |

レプリカに対するパーティション管理コントローラのソケットタイムアウトです。

controller.message.queue.size

| デフォルト | Int.MaxValue |

コントローラからブローカへの接続チャネル( controller-to-broker-channels )のバッファサイズです。

default.replication.factor

| デフォルト | 1 |

自動作成されたトピックのデフォルトレプリケーションファクタです。

replica.lag.time.max.ms

| デフォルト | 10000 |

フォロワがここで設定した時間内に取得リクエストを送信しなかった場合、 リーダはそのフォロワを ISR (in-sync replicas) から除去し、死んだものとして扱います。

replica.lag.max.messages

| デフォルト | 4000 |

ここで設定したメッセージ数よりレプリケーションが遅れた場合、 リーダはそのフォロワを ISR (in-sync replicas) から除去し、死んだものとして扱います。

replica.socket.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 30 * 1000 |

データ複製の為のリーダへのネットワークリクエストのソケットタイムアウトです。

replica.socket.receive.buffer.bytes

| デフォルト | 64 * 1024 |

データ複製の為のリーダへのネットワークリクエストのソケット受信バッファです。

replica.fetch.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 1024 * 1024 |

レプリカがリーダへ送信する取得リクエスト時の、 各パーティションについて取得を試行するメッセージのバイト数です。

replica.fetch.wait.max.ms

| デフォルト | 500 |

レプリカがリーダへ送信する取得リクエスト時の、リーダへデータが到達するまでの待機時間です。

replica.fetch.min.bytes

| デフォルト | 1 |

レプリカがリーダへ送信する取得リクエストに対する各取得レスポンスが想定する最小バイトです。

この設定に満たない場合は、 replica.fetch.wait.max.ms まで待機します。

num.replica.fetchers

| デフォルト | 1 |

リーダからメッセージを複製するのに使うスレッド数です。 この設定値を増やすとフォロワブローカの I/O 並列処理数が増加します。

replica.high.watermark.checkpoint.interval.ms

| デフォルト | 5000 |

各レプリカがリカバリ処理の為に自身のハイウォータマークを記録する頻度です。

fetch.purgatory.purge.interval.requests

| デフォルト | 1000 |

取得リクエストパーガトリの 9 解放間隔(リクエスト数)です。

producer.purgatory.purge.interval.requests

| デフォルト | 1000 |

プロデューサリクエストパーガトリ 9 の解放間隔(リクエスト数)です。

zookeeper.session.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 6000 |

ZooKeeper のセッションタイムアウトです。 ZooKeeperへのハートビートがこの期間失敗すると、そのサーバは死んだものとされます。 この値をあまりにも小さくしてしまうと、サーバが死んだと誤検知されてしまうかもしれませんし、 かといって大きくし過ぎると、本当に死んだサーバを認識するのに時間がかかるようになってしまいます。

zookeeper.connection.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 6000 |

クライアントが ZooKeeper との接続を確立するまでの最大待機時間です。

zookeeper.sync.time.ms

| デフォルト | 2000 |

ZooKeeper フォロワがリーダからどのくらい遅れ得るかです。

controlled.shutdown.enable

| デフォルト | true |

ブローカの制御シャットダウンを有効にします。 この設定が有効な場合、そのブローカはシャットダウン前に自身のリーダ権を全て他のブローカに移動させます。 これによりシャットダウン中のサービス不能期間を減らすことが出来ます。

controlled.shutdown.max.retries

| デフォルト | 3 |

制御シャットダウンが成功するまでのリトライ回数です。 この回数を超えて失敗すると、強制シャットダウンされます。

controlled.shutdown.retry.backoff.ms

| デフォルト | 5000 |

シャットダウンのリトライ時のバックオフ時間です。

auto.leader.rebalance.enable

| デフォルト | true |

この設定が有効な場合、コントローラは自動的にブローカ間でパーティションのリーダ権のバランシングを試みます。 バランシングは、定期的にリーダ権を各パーティションの「優先」レプリカに返却することによって行なわれます(「推奨」レプリカが存在する場合)。

leader.imbalance.per.broker.percentage

| デフォルト | 10 |

リーダのブローカ毎の偏りのパーセンテージです。 コントローラはブローカ毎にこの割合を超えた場合にリーダ権のリバランスを行います。

leader.imbalance.check.interval.seconds

| デフォルト | 300 |

リーダの偏りを検査する頻度です。

offset.metadata.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 4096 |

クライアントが自身のオフセットを記録するためのメタデータの最大容量です。

max.connections.per.ip

| デフォルト | Int.MaxValue |

ブローカが IP 毎に許可する接続数の最大値です。

max.connections.per.ip.overrides

| デフォルト |

IP またはホスト名を指定して、デフォルトの最大接続数を上書き出来ます。

connections.max.idle.ms

| デフォルト | 600000 |

アイドルコネクションタイムアウト、つまり、 サーバソケットプロセッサスレッドがこの値以上アイドル状態だった場合に接続を閉じます。

log.roll.jitter.{ms,hours}

| デフォルト | 0 |

logRollTimeMillis から減じられる最大ジッタです。

num.recovery.threads.per.data.dir

| デフォルト | 1 |

データディレクトリ毎に起動時のログリカバリやシャットダウン時のフラッシュに使用されるスレッド数です。

unclean.leader.election.enable

| デフォルト | true |

最終手段として ISR 以外のレプリカをリーダとして選択することを許可するかどうかを示します。 これによりデータがロストする可能性があります。

delete.topic.enable

| デフォルト | false |

トピックを削除出来るようにします。

offsets.topic.num.partitions

| デフォルト | 50 |

オフセットコミットトピックのパーティション数です。 デプロイ後にこの値を変えることは現在サポートされていないため、 プロダクション環境ではより大きい数値(例えば 100-200)に設定することを推奨します。

offsets.topic.retention.minutes

| デフォルト | 1440 |

この値よりも古いオフセットは削除対象としてマークされます。 ログクリーナがオフセットトピックのコンパクションを実行した際に、実際に削除されます。

offsets.retention.check.interval.ms

| デフォルト | 600000 |

オフセットマネージャが古くなったオフセットを検査する頻度です。

offsets.topic.replication.factor

| デフォルト | 3 |

オフセットコミットトピックのレプリケーションファクタです。 高可用性を保証するにはこの値をより高い値(3や4等)に設定することを推奨します。 レプリケーションファクタよりも少ないブローカしかいな場合にオフセットトピックが作成された場合は、 この設定よりも少ないレプリカしか作られません。

offsets.topic.segment.bytes

| デフォルト | 104857600 |

オフセットトピックのセグメントサイズです。 オフセットトピックはコンパクションされたトピックを使う為、 ログコンパクションとロードを高速に行ない易くするためには この設定値は比較的小さな値にしておくべきです。

offsets.load.buffer.size

| デフォルト | 5242880 |

ブローカがあるコンシューマグループのオフセットマネージャになった時に (つまり、 オフセットトピックのリーダになった時に)、オフセットのロードが行なわれます。 オフセットマネージャのキャッシュにオフセットをロードする際に、 ここで設定したバッチサイズ(バイト数指定)を参照してオフセットセグメントからの読み込みを行ないます。

offsets.commit.required.acks

| デフォルト | -1 |

オフセットコミットが受け入れられる為に必要な Ack 数です。 プロデューサの Ack 設定と似たようなものです。 通常はデフォルト値から変更すべきではありません。

offsets.commit.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 5000 |

このタイムアウト分か、必要なレプリカがオフセットコミットを受信するまでオフセットコミットは遅延されます。 プロデューサのリクエストタイムアウトと似たようなものです。

Topic-level configuration

トピック関連の設定には、

グローバルなデフォルト設定と、

トピック毎にオーバライドするための設定の二つが有ります。

トピック毎の設定が与えられなければグローバルデフォルト値が使用されます。

トピック作成時に一つ以上の --config オプションを与えることでオーバライド出来ます。

my-topic という名前のトピックを、

最大メッセージサイズとフラッシュレートをカスタマイズして作成する例を以下に示します:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --create --topic my-topic --partitions 1

--replication-factor 1 --config max.message.bytes=64000 --config flush.messages=1

オーバライドはオルター(変更)コマンドを利用することで後から変更・設定することも出来ます。 my-topic の最大メッセージサイズを更新する例を以下に示します:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --alter --topic my-topic --config max.message.bytes=128000

オーバライド設定を削除するには以下のようにします:

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --alter --topic my-topic --deleteConfig max.message.bytes

以下はトピックレベルの設定です。 プロパティに対応するサーバのデフォルト設定は「サーバデフォルトプロパティ」の列にあります。 このサーバ設定を変更することで、オーバライド未指定時にトピックに設定されるデフォルト値を変更することが出来ます。

cleanup.policy

| デフォルト | delete |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.cleanup.policy |

delete または compact を設定出来ます。

古くなったログセグメントに適用される保持ポリシーを指定します。

デフォルトポリシー( delete )では、保持期限を過ぎるか容量制限に達した場合に、古いセグメントは破棄されます。

compact ポリシーではトピックに対して ログコンパクション が行われます。

delete.retention.ms

| デフォルト | 86400000 (24 時間) |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.cleaner.delete.retention.ms |

ログコンパクションされたトピックの削除トゥームストーンマーカを保持する時間です。

ログコンパクション されたトピックの削除トゥームストーンマーカを保持する期間です。 最終段階の有効なスナップショットを確実に得る為にオフセット 0 から読み込みを開始する場合、 コンシューマはこの期間内に読み込みを完了させる必要があります (さもなければ、コンシューマの走査が完了する前に 削除トゥームストーンマーカが回収されてしまう可能性が有ります。)。

flush.messages

| デフォルト | None |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.flush.interval.messages |

ログに書き込むデータをディスクに強制的に fsync するする間隔を指定出来ます。 例えば、この値を 1 にすると全メッセージについて都度 fsync するようになります; もし 5 にすると、5メッセージ毎に fsync を行うようになります。 通常はこの設定は指定せず、堅牢性は複製機構によって担保するようにすること推奨します。 オペレーティングシステムのより効率的なバックグラウンドのフラッシュ性能に委ねましょう。 この設定値はトピック毎に上書き可能です( トピックレベルの設定 を参照)。 10

flush.ms

| デフォルト | None |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.flush.interval.ms |

ログに書き込むデータをディスクに強制的に fsync するする間隔を指定出来ます。 例えば、この値を 1000 にすると 1000 ms 経過毎に fsync するようになります。 通常はこの設定は指定せず、堅牢性は複製機構によって担保するようにすること推奨します。 オペレーティングシステムのより効率的なバックグラウンドのフラッシュ性能に委ねましょう。

index.interval.bytes

| デフォルト | 4096 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.index.interval.bytes |

この設定はKafkaがオフセットインデックスにインデックスエントリを追加する頻度を制御します。 デフォルト設定ではおよそ 4096 バイト毎にメッセージをインデックスするようになっています。 より多くインデクシングすればする程、 読み込み時にログ上の正確な位置を知ることが出来るようになりますが、 その分インデックスサイズは大きくなります。 おそらくこの値を変更する必要はないでしょう。

max.message.bytes

| デフォルト | 1,000,000 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | message.max.bytes |

そのトピックに追記出来る最大メッセージサイズです。 この値を増やすならば、コンシューマの最大取得サイズも増やさなければ、 メッセージを取得出来なくなってしまうため注意が必要です。

min.cleanable.dirty.ratio

| デフォルト | 0.5 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.cleaner.min.cleanable.ratio |

ログコンパクション が有効なときの、ログコンパクタがログをクリーンする頻度を設定します。 デフォルトでは50%以上のログがコンパクションされていた場合はクリーニングを行ないません。 この比率はログの重複により無駄に使用される最大スペースを設定します (50%だと、多くて50%のログが重複している可能性がある、ということです)。 より高い比率に設定すれば、少ない回数で、より効率的なクリーニングが行われることになりますが、 それは同時にログが無駄に使用するスペースがより多くなるということにもなります。 11

min.insync.replicas

| デフォルト | 1 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | min.insync.replicas 12 |

プロデューサが request.required.acks を -1 に設定していた場合、

その書き込みが成功したと判断される為には、

最低限この設定値以上の複製が受領されなければなりません。

これが満たされない場合、プロデューサは例外を発生させます

( NotEnoughReplicas もしくは NotEnoughReplicasAfterAppend)。

min.insync.replicas と request.required.acks を共に設定することで、

より強力な堅牢性を保証することが出来ます。

典型的なシナリオでは、レプリケーションファクタ 3 のトピックを作成し、

min.insync.replicas を 2 に設定した上で、

request.required.acks を -1 に設定してプロデュースする、というようになるでしょう。

こうすることで、書込みを受領出来ない複製が多数を占めた場合に、

プロデューサが例外を投げることを保証出来ます。

retention.bytes

| デフォルト | None |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.retention.bytes |

ログの保持ポリシーが delete の場合に、

ログ容量がこの設定値を超えると、容量確保の為に古いログセグメントを破棄します。

デフォルトでは容量制限は無く、時間による制限のみです。

retention.ms

| デフォルト | 7 日 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.retention.minutes |

ログの保持ポリシーが delete の場合に、

ログがこの設定値より古くなると、容量確保の為に古いログセグメントを破棄します。

これはコンシューマがデータを取得するまでの期間に関する

SLA(service level agreement, サービス品質保証)を表わしています。

segment.bytes

| デフォルト | 1 GB |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.segment.bytes |

ログのセグメントファイルサイズを制御します。 保持及びクリーニングは常に1ファイルごとに行なわれるため、 セグメントファイルサイズが大きくなれば扱うファイル数は少なくなりますが、 ファイル保持制御の粒度は荒くなってしまいます。

segment.index.bytes

| デフォルト | 10 MB |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.index.size.max.bytes |

オフセットとファイルの位置を対応づけるインデックスのサイズを制御します。 このインデックスファイルは事前に確保され、ログロールの際に縮小されます。 通常はこの値を変更すべきではありません。

segment.ms

| デフォルト | 7 days |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.roll.hours |

セグメントファイルが古いデータの削除、またはコンパクション条件を満たしていない場合でも、 この期間が過ぎると強制的に新たなセグメントファイルが作成されます。

segment.jitter.ms

| デフォルト | 0 |

| サーバデフォルトプロパティ | log.roll.jitter.{ms,hours} |

logRollTimeMillis から減じられる最大ジッタです。

3.2 Consumer Configs

The essential consumer configurations are the following:

group.idzookeeper.connect

More details about consumer configuration can be found in the scala class kafka.consumer.ConsumerConfig.

group.id

| デフォルト |

A string that uniquely identifies the group of consumer processes to which this consumer belongs. By setting the same group id multiple processes indicate that they are all part of the same consumer group.

zookeeper.connect

| デフォルト |

Specifies the ZooKeeper connection string in the form hostname:port where host and port are the host and port of a ZooKeeper server. To allow connecting through other ZooKeeper nodes when that ZooKeeper machine is down you can also specify multiple hosts in the form hostname1:port1,hostname2:port2,hostname3:port3. The server may also have a ZooKeeper chroot path as part of it's ZooKeeper connection string which puts its data under some path in the global ZooKeeper namespace. If so the consumer should use the same chroot path in its connection string. For example to give a chroot path of /chroot/path you would give the connection string as hostname1:port1,hostname2:port2,hostname3:port3/chroot/path.

consumer.id

| デフォルト | null |

Generated automatically if not set.

socket.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 30 * 1000 |

The socket timeout for network requests. The actual timeout set will be max.fetch.wait + socket.timeout.ms.

socket.receive.buffer.bytes

| デフォルト | 64 * 1024 |

The socket receive buffer for network requests

fetch.message.max.bytes

| デフォルト | 1024 * 1024 |

取得リクエスト時に、各トピックパーティションからメッセージを何バイト取得を試みるか、を設定します。 ここで設定されたバイト数分、各トピック毎にメモリに読み込まれるため、 コンシューマのメモリ使用を制御したい場合はこのプロパティを調整することになります。 取得リクエストサイズは少なくとも サーバが許容する最大メッセージサイズ よりも大きくする必要があります。 さもなければ、コンシューマが取得出来ないほど大きなメッセージをプロデューサが送ることが出来てしまいます。

num.consumer.fetchers

| デフォルト | 1 |

The number fetcher threads used to fetch data.

auto.commit.enable

| デフォルト | true |

If true, periodically commit to ZooKeeper the offset of messages already fetched by the consumer. This committed offset will be used when the process fails as the position from which the new consumer will begin.

auto.commit.interval.ms

| デフォルト | 60 * 1000 |

The frequency in ms that the consumer offsets are committed to zookeeper.

queued.max.message.chunks

| デフォルト | 2 |

Max number of message chunks buffered for consumption. Each chunk can be up to fetch.message.max.bytes.

rebalance.max.retries

| デフォルト | 4 |

When a new consumer joins a consumer group the set of consumers attempt to "rebalance" the load to assign partitions to each consumer. If the set of consumers changes while this assignment is taking place the rebalance will fail and retry. This setting controls the maximum number of attempts before giving up.

fetch.min.bytes

| デフォルト | 1 |

The minimum amount of data the server should return for a fetch request. If insufficient data is available the request will wait for that much data to accumulate before answering the request.

fetch.wait.max.ms

| デフォルト | 100 |

The maximum amount of time the server will block before answering the fetch request if there isn't sufficient data to immediately satisfy fetch.min.bytes

rebalance.backoff.ms

| デフォルト | 2000 |

Backoff time between retries during rebalance.

refresh.leader.backoff.ms

| デフォルト | 200 |

Backoff time to wait before trying to determine the leader of a partition that has just lost its leader.

auto.offset.reset

| デフォルト | largest |

What to do when there is no initial offset in ZooKeeper or if an offset is out of range:

- smallest

- automatically reset the offset to the smallest offset

- largest

- automatically reset the offset to the largest offset

- anything else

- throw exception to the consumer

consumer.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | -1 |

Throw a timeout exception to the consumer if no message is available for consumption after the specified interval

exclude.internal.topics

| デフォルト | true |

Whether messages from internal topics (such as offsets) should be exposed to the consumer.

partition.assignment.strategy

| デフォルト | range |

Select a strategy for assigning partitions to consumer streams. Possible values: range, roundrobin.

client.id

| デフォルト | group id value |

The client id is a user-specified string sent in each request to help trace calls. It should logically identify the application making the request.

zookeeper.session.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 6000 |

ZooKeeper session timeout. If the consumer fails to heartbeat to ZooKeeper for this period of time it is considered dead and a rebalance will occur.

zookeeper.connection.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 6000 |

The max time that the client waits while establishing a connection to zookeeper.

zookeeper.sync.time.ms

| デフォルト | 2000 |

How far a ZK follower can be behind a ZK leader

offsets.storage

| デフォルト | zookeeper |

Select where offsets should be stored (zookeeper or kafka).

offsets.channel.backoff.ms

| デフォルト | 1000 |

The backoff period when reconnecting the offsets channel or retrying failed offset fetch/commit requests.

offsets.channel.socket.timeout.ms

| デフォルト | 10000 |

Socket timeout when reading responses for offset fetch/commit requests. This timeout is also used for ConsumerMetadata requests that are used to query for the offset manager.

offsets.commit.max.retries

| デフォルト | 5 |

Retry the offset commit up to this many times on failure. This retry count only applies to offset commits during shut-down. It does not apply to commits originating from the auto-commit thread. It also does not apply to attempts to query for the offset coordinator before committing offsets. i.e., if a consumer metadata request fails for any reason, it will be retried and that retry does not count toward this limit.

dual.commit.enabled

| デフォルト | true |

If you are using "kafka" as offsets.storage, you can dual commit offsets to ZooKeeper (in addition to Kafka). This is required during migration from zookeeper-based offset storage to kafka-based offset storage. With respect to any given consumer group, it is safe to turn this off after all instances within that group have been migrated to the new version that commits offsets to the broker (instead of directly to ZooKeeper).

partition.assignment.strategy

| デフォルト | range |

Select between the "range" or "roundrobin" strategy for assigning partitions to consumer streams.

The round-robin partition assignor lays out all the available partitions and all the available consumer threads. It then proceeds to do a round-robin assignment from partition to consumer thread. If the subscriptions of all consumer instances are identical, then the partitions will be uniformly distributed. (i.e., the partition ownership counts will be within a delta of exactly one across all consumer threads.) Round-robin assignment is permitted only if: (a) Every topic has the same number of streams within a consumer instance (b) The set of subscribed topics is identical for every consumer instance within the group.

Range partitioning works on a per-topic basis. For each topic, we lay out the available partitions in numeric order and the consumer threads in lexicographic order. We then divide the number of partitions by the total number of consumer streams (threads) to determine the number of partitions to assign to each consumer. If it does not evenly divide, then the first few consumers will have one extra partition.

3.3 Producer Configs

Essential configuration properties for the producer include:

metadata.broker.listrequest.required.acksproducer.typeserializer.class

More details about producer configuration can be found in the scala class kafka.producer.ProducerConfig.

metadata.broker.list

| Default |

This is for bootstrapping and the producer will only use it for getting metadata (topics, partitions and replicas). The socket connections for sending the actual data will be established based on the broker information returned in the metadata. The format is host1:port1,host2:port2, and the list can be a subset of brokers or a VIP pointing to a subset of brokers.

request.required.acks

| Default | 0 |

This value controls when a produce request is considered completed. Specifically, how many other brokers must have committed the data to their log and acknowledged this to the leader? Typical values are

- 0, which means that the producer never waits for an acknowledgement from the broker (the same behavior as 0.7). This option provides the lowest latency but the weakest durability guarantees (some data will be lost when a server fails).

- 1, which means that the producer gets an acknowledgement after the leader replica has received the data. This option provides better durability as the client waits until the server acknowledges the request as successful (only messages that were written to the now-dead leader but not yet replicated will be lost).

- -1, The producer gets an acknowledgement after all in-sync replicas have received the data. This option provides the greatest level of durability. However, it does not completely eliminate the risk of message loss because the number of in sync replicas may, in rare cases, shrink to 1. If you want to ensure that some minimum number of replicas (typically a majority) receive a write, then you must set the topic-level min.insync.replicas setting. Please read the Replication section of the design documentation for a more in-depth discussion.

request.timeout.ms

| Default | 10000 |

The amount of time the broker will wait trying to meet the request.required.acks requirement before sending back an error to the client.

producer.type

| Default | sync |

This parameter specifies whether the messages are sent asynchronously in a background thread. Valid values are (1) async for asynchronous send and (2) sync for synchronous send. By setting the producer to async we allow batching together of requests (which is great for throughput) but open the possibility of a failure of the client machine dropping unsent data.

serializer.class

| Default | kafka.serializer.DefaultEncoder |

The serializer class for messages. The default encoder takes a byte[] and returns the same byte[].

key.serializer.class

| Default |

The serializer class for keys (defaults to the same as for messages if nothing is given).

partitioner.class

| Default | kafka.producer.DefaultPartitioner |

The partitioner class for partitioning messages amongst sub-topics. The default partitioner is based on the hash of the key.

compression.codec

| Default | none |

This parameter allows you to specify the compression codec for all data generated by this producer. Valid values are "none", "gzip" and "snappy".

compressed.topics

| Default | null |

This parameter allows you to set whether compression should be turned on for particular topics. If the compression codec is anything other than NoCompressionCodec, enable compression only for specified topics if any. If the list of compressed topics is empty, then enable the specified compression codec for all topics. If the compression codec is NoCompressionCodec, compression is disabled for all topics

message.send.max.retries

| Default | 3 |

This property will cause the producer to automatically retry a failed send request. This property specifies the number of retries when such failures occur. Note that setting a non-zero value here can lead to duplicates in the case of network errors that cause a message to be sent but the acknowledgement to be lost.

retry.backoff.ms

| Default | 100 |

Before each retry, the producer refreshes the metadata of relevant topics to see if a new leader has been elected. Since leader election takes a bit of time, this property specifies the amount of time that the producer waits before refreshing the metadata.

topic.metadata.refresh.interval.ms

| Default | 600 * 1000 |

The producer generally refreshes the topic metadata from brokers when there is a failure (partition missing, leader not available…). It will also poll regularly (default: every 10min so 600000ms). If you set this to a negative value, metadata will only get refreshed on failure. If you set this to zero, the metadata will get refreshed after each message sent (not recommended). Important note: the refresh happen only AFTER the message is sent, so if the producer never sends a message the metadata is never refreshed

queue.buffering.max.ms

| Default | 5000 |

Maximum time to buffer data when using async mode. For example a setting of 100 will try to batch together 100ms of messages to send at once. This will improve throughput but adds message delivery latency due to the buffering.

queue.buffering.max.messages

| Default | 10000 |

The maximum number of unsent messages that can be queued up the producer when using async mode before either the producer must be blocked or data must be dropped.

queue.enqueue.timeout.ms

| Default | -1 |

The amount of time to block before dropping messages when running in async mode and the buffer has reached queue.buffering.max.messages. If set to 0 events will be enqueued immediately or dropped if the queue is full (the producer send call will never block). If set to -1 the producer will block indefinitely and never willingly drop a send.

batch.num.messages

| Default | 200 |

The number of messages to send in one batch when using async mode. The producer will wait until either this number of messages are ready to send or queue.buffer.max.ms is reached.

send.buffer.bytes

| Default | 100 * 1024 |

Socket write buffer size

client.id

| Default | "" |

The client id is a user-specified string sent in each request to help trace calls. It should logically identify the application making the request.

3.4 New Producer Configs

We are working on a replacement for our existing producer. The code is available in trunk now and can be considered beta quality. Below is the configuration for the new producer. 13

bootstrap.servers

| Type | list |

| Default | |

| Importance | high |

A list of host/port pairs to use for establishing the initial connection to the Kafka cluster. Data will be load balanced over all servers irrespective of which servers are specified here for bootstrapping—this list only impacts the initial hosts used to discover the full set of servers. This list should be in the form host1:port1,host2:port2,…. Since these servers are just used for the initial connection to discover the full cluster membership (which may change dynamically), this list need not contain the full set of servers (you may want more than one, though, in case a server is down). If no server in this list is available sending data will fail until on becomes available.

acks

| Type | string |

| Default | 1 |

| Importance | high |

The number of acknowledgments the producer requires the leader to have received before considering a request complete. This controls the durability of records that are sent. The following settings are common:

acks=0If set to zero then the producer will not wait for any acknowledgment from the server at all. The record will be immediately added to the socket buffer and considered sent. No guarantee can be made that the server has received the record in this case, and theretriesconfiguration will not take effect (as the client won't generally know of any failures). The offset given back for each record will always be set to -1.acks=1This will mean the leader will write the record to its local log but will respond without awaiting full acknowledgement from all followers. In this case should the leader fail immediately after acknowledging the record but before the followers have replicated it then the record will be lost.acks=allThis means the leader will wait for the full set of in-sync replicas to acknowledge the record. This guarantees that the record will not be lost as long as at least one in-sync replica remains alive. This is the strongest available guarantee.- Other settings such as

acks=2are also possible, and will require the given number of acknowledgements but this is generally less useful.

buffer.memory

| Type | long |

| Default | 33554432 |

| Importance | high |

The total bytes of memory the producer can use to buffer records waiting to be sent to the server. If records are sent faster than they can be delivered to the server the producer will either block or throw an exception based on the preference specified by block.on.buffer.full.

This setting should correspond roughly to the total memory the producer will use, but is not a hard bound since not all memory the producer uses is used for buffering. Some additional memory will be used for compression (if compression is enabled) as well as for maintaining in-flight requests.

compression.type

| Type | string |

| Default | none |

| Importance | high |

The compression type for all data generated by the producer. The default is none (i.e. no compression). Valid values are none, gzip, or snappy. Compression is of full batches of data, so the efficacy of batching will also impact the compression ratio (more batching means better compression).

retries

| Type | int |

| Default | 0 |

| Importance | high |

Setting a value greater than zero will cause the client to resend any record whose send fails with a potentially transient error. Note that this retry is no different than if the client resent the record upon receiving the error. Allowing retries will potentially change the ordering of records because if two records are sent to a single partition, and the first fails and is retried but the second succeeds, then the second record may appear first.

batch.size

| Type | int |

| Default | 16384 |

| Importance | medium |

The producer will attempt to batch records together into fewer requests whenever multiple records are being sent to the same partition. This helps performance on both the client and the server. This configuration controls the default batch size in bytes.

No attempt will be made to batch records larger than this size.

Requests sent to brokers will contain multiple batches, one for each partition with data available to be sent.

A small batch size will make batching less common and may reduce throughput (a batch size of zero will disable batching entirely). A very large batch size may use memory a bit more wastefully as we will always allocate a buffer of the specified batch size in anticipation of additional records.

client.id

| Type | string |

| Default | |

| Importance | medium |

The id string to pass to the server when making requests. The purpose of this is to be able to track the source of requests beyond just ip/port by allowing a logical application name to be included with the request. The application can set any string it wants as this has no functional purpose other than in logging and metrics.

linger.ms

| Type | long |

| Default | 0 |

| Importance | medium |

The producer groups together any records that arrive in between request transmissions into a single batched request. Normally this occurs only under load when records arrive faster than they can be sent out. However in some circumstances the client may want to reduce the number of requests even under moderate load. This setting accomplishes this by adding a small amount of artificial delay—that is, rather than immediately sending out a record the producer will wait for up to the given delay to allow other records to be sent so that the sends can be batched together. This can be thought of as analogous to Nagle's algorithm in TCP. This setting gives the upper bound on the delay for batching: once we get batch.size worth of records for a partition it will be sent immediately regardless of this setting, however if we have fewer than this many bytes accumulated for this partition we will 'linger' for the specified time waiting for more records to show up. This setting defaults to 0 (i.e. no delay). Setting linger.ms=5, for example, would have the effect of reducing the number of requests sent but would add up to 5ms of latency to records sent in the absense of load.

max.request.size

| Type | int |

| Default | 1048576 |

| Importance | medium |

The maximum size of a request. This is also effectively a cap on the maximum record size. Note that the server has its own cap on record size which may be different from this. This setting will limit the number of record batches the producer will send in a single request to avoid sending huge requests.

receive.buffer.bytes

| Type | int |

| Default | 32768 |

| Importance | medium |

The size of the TCP receive buffer to use when reading data

send.buffer.bytes

| Type | int |

| Default | 131072 |

| Importance | medium |

The size of the TCP send buffer to use when sending data

timeout.ms

| Type | int |

| Default | 30000 |

| Importance | medium |

The configuration controls the maximum amount of time the server will wait for acknowledgments from followers to meet the acknowledgment requirements the producer has specified with the acks configuration. If the requested number of acknowledgments are not met when the timeout elapses an error will be returned. This timeout is measured on the server side and does not include the network latency of the request.

block.on.buffer.full

| Type | boolean |

| Default | true |

| Importance | low |

When our memory buffer is exhausted we must either stop accepting new records (block) or throw errors. By default this setting is true and we block, however in some scenarios blocking is not desirable and it is better to immediately give an error. Setting this to false will accomplish that: the producer will throw a BufferExhaustedException if a recrord is sent and the buffer space is full.

metadata.fetch.timeout.ms

| Type | long |

| Default | 60000 |

| Importance | low |

The first time data is sent to a topic we must fetch metadata about that topic to know which servers host the topic's partitions. This configuration controls the maximum amount of time we will block waiting for the metadata fetch to succeed before throwing an exception back to the client.

metadata.max.age.ms

| Type | long |

| Default | 300000 |

| Importance | low |

The period of time in milliseconds after which we force a refresh of metadata even if we haven't seen any partition leadership changes to proactively discover any new brokers or partitions.

metric.reporters

| Type | list |

| Default | [] |

| Importance | low |

A list of classes to use as metrics reporters. Implementing the MetricReporter interface allows plugging in classes that will be notified of new metric creation. The JmxReporter is always included to register JMX statistics.

metrics.num.samples

| Type | int |

| Default | 2 |

| Importance | low |

The number of samples maintained to compute metrics.

metrics.sample.window.ms

| Type | long |

| Default | 30000 |